The Biden administration has backed away from supporting caps on plastic production as part of the United Nations’ Global Plastics Treaty.

Representatives of five environmental groups say White House officials told representatives of advocacy groups in a closed-door meeting last week that mandatory production caps are not effective for INC-5 He said he did not think of it as a possible “landing point.” The final round of plastics treaty negotiations is scheduled to be held in Busan, South Korea, later this month. Instead, staffers reportedly said the U.S. delegation supports a “flexible” approach in which countries set voluntary targets to reduce plastic production.

This represents a reversal of what the same group said at a similar press conference in August. At the time, representatives of the Biden administration expressed hope that the United States would join countries such as Norway, Peru, and the United Kingdom in supporting limits on plastic production.

Following the August meeting, Reuters reported The US “supports a global treaty that would reduce the amount of new plastic produced each year,” the Biden administration said, confirming the Reuters report was “accurate.”

After a recent briefing, a spokesperson for the White House Council on Environmental Quality told Grist that U.S. negotiators support the idea of ”an ambitious global ‘North Star’ goal” to reduce plastic production. However, he said, “I don’t think this is correct.” It sets production limits and does not support such limits. ”

“We believe there are many different paths to achieving reductions in plastic production and consumption,” the spokesperson said. “We intend to approach INC-5 with flexibility in how we achieve that, and we are optimistic that we can win with a strong lever that signals change to the market.”

Joe Banner, co-founder and co-director of the Descendant Project, a nonprofit that advocates for fence-line communities in Louisiana’s Cancer Alley, said the announcement was “shocking.” .

“I thought we were on the same page when it came to closing the cap on plastic and reducing production,” she said. “But it was clear we weren’t.”

Frankie Orona, executive director of the Society of Native Nations, a nonprofit organization that advocates for environmental justice and the preservation of indigenous cultures, called the news “absolutely devastating.” He added, “Those two hours of that meeting felt like two days of my life.”

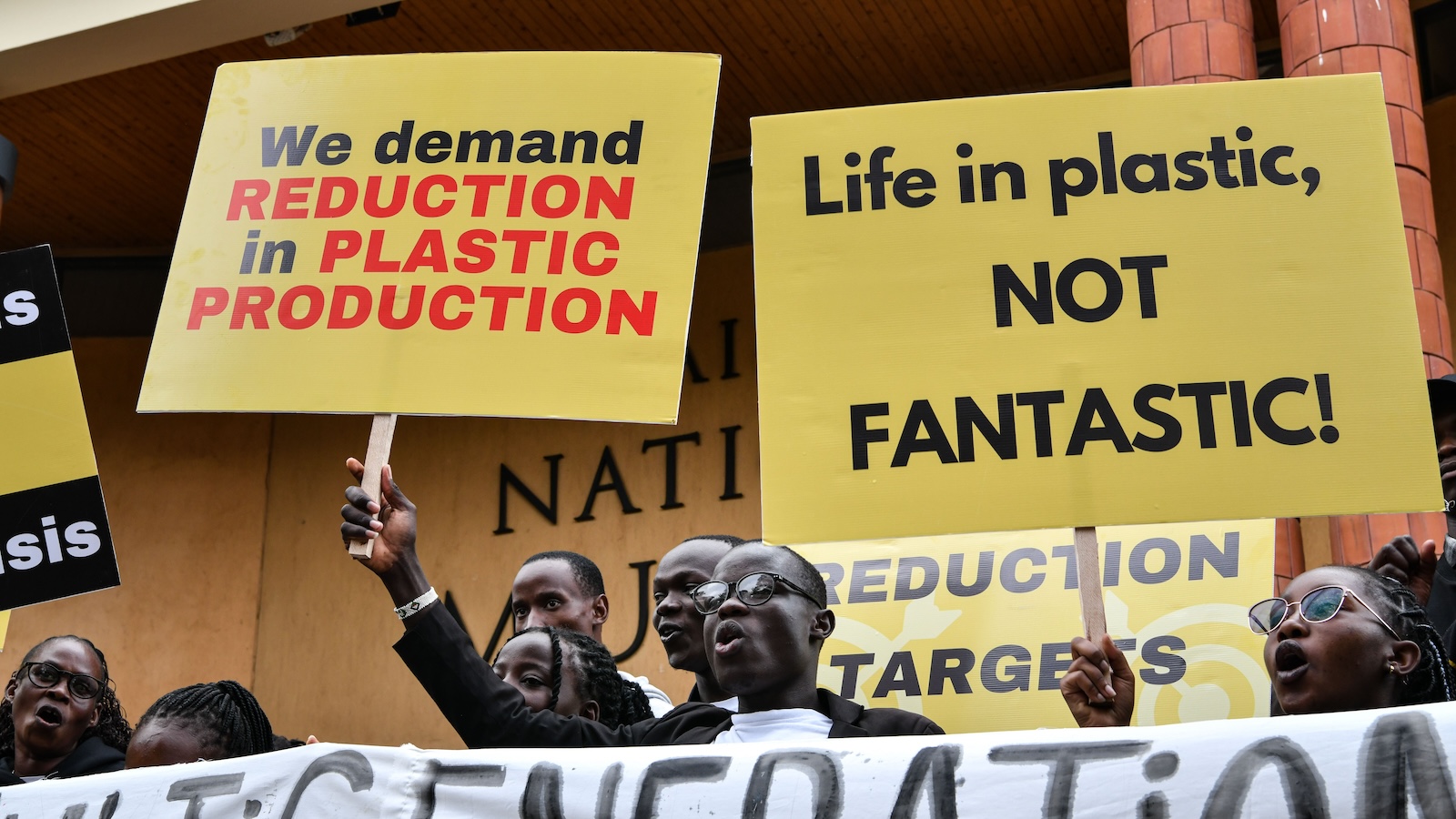

James Wakibia/SOPA Images/LightRocket (via Getty Images)

The situation illustrates a central conflict arising from negotiations over the treaty, which the United Nations agreed to negotiate two years ago to “end plastic pollution.” Participants questioned whether the agreement should focus on managing plastic waste, such as through ocean cleanups and increasing recycling rates, or on curbing the rate of increase in plastic production. Not agreed.

almost 70 countrieswith scientist and environmental groups favor the latter. They say it’s futile to clean up plastic waste while more and more plastic waste is being created. But a vocal group of oil exporting countries is demanding a lower target treaty, using consensus-based voting criteria to delay negotiations. In addition to excluding production limits, these countries want a treaty that recognizes voluntary national goals rather than binding global rules.

It is not entirely clear which policy the United States currently supports. A White House spokesperson told Grist that he wants to ensure the treaty “addresses the supply of primary plastic polymers,” which could mean anything from taxing plastic production to banning individual plastic products. He said it is possible. These kinds of so-called market instruments could push down the demand for more plastics, but the certainty is much lower than that of quantitative production limits. Björn Boehler, executive director of the nonprofit International Pollutant Removal Network, said the U.S. could technically “address” the plastic supply by lowering the industry’s expected growth rate. . That way, the amount of plastic produced could continue to increase every year.

“The U.S. statement is extremely vague,” he said. “They were not the main actors in making this treaty meaningful.”

To the extent that the White House’s latest announcement is a clarification and not an outright reversal (something staffers reportedly insisted was the case), Banner said the Biden administration He said that he should have made his position more clear immediately after the meeting in January. “Back in August, we definitely said ‘cap,’ and it wasn’t fixed,” she said. “If there was a misunderstanding, it should have been corrected a long time ago.”

Another obvious change in US strategy concerns the chemicals used in plastics. Back in August, the White House confirmed in a Reuters report that it supported creating a list of plastic-related chemicals that would be banned or restricted. Going forward, negotiators will support a list that includes plastics product that contain those chemicals. Environmental groups believe this approach is not very effective because there are so many different types of plastic products and product manufacturers do not always have complete information about the chemicals used by their suppliers.

Plastic chemicals are inevitable – and they’re disrupting our hormones

Orona said focusing on products will push the conversation downstream from petrochemical refineries and plastic manufacturing facilities that disproportionately pollute poor communities of color.

“It’s very derogatory and very disrespectful,” he said. “I wanted to grab a pillow and scream into it and cry tears for my community.”

In the upcoming treaty negotiations, environmental groups told Grist that the U.S. should “stand down.” Given that the incoming Trump administration will not support the treaty and the Republican-controlled Senate is unlikely to ratify it, some proponents believe that high-minded countries could win U.S. support. Some people want to focus more on driving more results than on things. An ambitious version of the treaty is possible. A spokesperson for the non-profit organization Break Free from Plastic said: “We hope that other parts of the world will move forward,” especially the European Union, small island developing states and the Association of African States. I sent a message.

Viola Wagii, environmental health and justice program director for the nonprofit Alaska Community Action on Toxics, is a tribal member of the Savonga Indian Village on Sibukak Island off the state’s west coast. She linked the weak plastics agreement to the direct impacts facing island communities, such as climate change (to which plastic production contributes) and microplastic pollution. in the arctic ocean It affects marine life and atmospheric dynamics. Dumping harmful plastic chemicals in the far northern hemisphere.

The United States “must ensure that we take steps to protect the voices of the most vulnerable,” including indigenous peoples, workers, waste pickers and future generations, she said. As an Indigenous grandmother, she expressed particular concern about plastic chemicals that have endocrine-disrupting properties. May affect children’s neurodevelopment. “If our children cannot learn, how can we pass on our language, our creation story, our songs and dances, our traditions and culture?”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25697397/STK071_APPLE_N.jpg?w=150&resize=150,150&ssl=1)