20 years have passed Since the paper was published in the journal Science The team found that tiny plastic fragments and fibres, which they dub “microplastics”, are accumulating in the environment.

This paper opened up an entirely new field of research, and since then, over 7,000 studies have been published demonstrating the pervasiveness of microplastics in the environment, wildlife and people.

So what did we learn? Paper published todayan international group of experts, including me, summarises the current state of knowledge.

This means that microplastics are widespread, accumulating in even the most remote parts of the planet, and there is evidence of toxic effects at all levels of biological systems, from tiny insects at the bottom of the food chain to apex predators.

Microplastics are widespread in food and drink and can be found throughout the human body, and evidence of their harmful effects is emerging.

The scientific evidence is now more than sufficient that collective global action is urgently needed to address microplastics, and the issue is more pressing than ever.

Small particles, big problems

Microplastics are generally recognised as plastic particles with a side length of 5mm or less.

Some microplastics are intentionally added to products, such as microbeads in facial soaps.

Others are produced unintentionally when larger plastic products break down, such as the fibres released when you wash a polyester fleece jacket.

Studies have identified the main sources of microplastics as follows:

- Cosmetic detergent

- Synthetic

- Car Tires

- Plastic Coated Fertilizer

- Plastic film used as mulch in agriculture

- Fishing rope and net

- “Rubber chip infill” used in artificial turf

- Plastic recycling.

Science has yet to determine how quickly larger plastics break down into microplastics.Nanoplastics“ – Even smaller particles that are invisible to the naked eye.

Measuring the threat of microplastics

Assessing the amount of microplastics in the air, soil, and water is difficult, but researchers have been trying.

for example, Research in 2020 It is estimated that between 800,000 and 3 million tonnes of microplastics enter the Earth’s oceans each year.

and Recent Reports They suggest that the amount of water leaking into the land environment could be three to ten times greater than the amount leaking into the ocean, which, if correct, would total 10 to 40 million tonnes.

And there’s more bad news: By 2040, the release of microplastics into the environment will More than twice as muchEven if humans stopped microplastics from entering the environment, the breakdown of larger plastics would continue.

Microplastics are Over 1,300 animal speciesThis includes fish, mammals, birds and insects.

Some animals mistake plastic particles for food and ingest them, which can lead to intestinal blockages and other problems. Chemicals contained in plastics can be released and harm animals, or animals that become attached to plastic can be harmed.

Invaders in the body

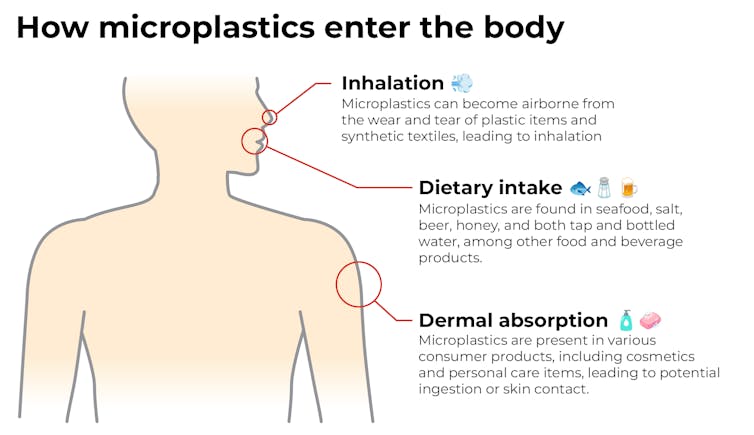

Microplastics are in the water we drink, the air we breathe, and The food we eat – Seafood, table salt, honey, sugar, beer, tea, etc.

Contamination can occur in the environment or as a result of food processing, packaging, and handling.

More data is needed on microplastics in human foods, including terrestrial animal products, grains, cereals, fruits, vegetables, beverages, spices, and oils and fats.

Concentrations of microplastics in food vary widely, and human exposure levels around the world are Changes tooHowever, some estimates, such as for humans, We consume the equivalent of a credit card’s worth of plastic every weekteeth Exaggeration.

With improvements in equipment, scientists have identified smaller and smaller particles. Scientists have found microplastics in our lungs, liver, kidneys, blood and reproductive organs. They pass through the protective barriers of our brains and hearts.

While some microplastics are excreted through urine, feces and lungs, many remain in the body for long periods of time.

So what impact does this have on the health of humans and other organisms? Over the years, scientists have changed the way they measure this.

Initially, they used high doses of microplastics in their lab tests, and now they are using more realistic doses that more accurately represent what humans and other organisms are actually exposed to.

Microplastics have different properties – they contain different chemicals, they interact differently with liquids and sunlight, and they also vary from one species to another, including humans.

This makes it difficult for scientists to conclusively link exposure to microplastics and their effects.

With regard to humans, progress is being made: in the coming years we can expect to have clearer information about its effects on our bodies, including:

- inflammation

- Oxidative stress (cell-damaging free radicals and antioxidant imbalance)

- Immune response

- Genotoxicity – The genetic information in cells is damaged, causing mutations, cancer.

What can we do?

Public concern about microplastics is growing, and this is compounded by the fact that it is nearly impossible to remove them from the environment, which means we are likely to be exposed to them over the long term.

Microplastic pollution is the result of human actions and decisions: we created the problem and now we must create the solution.

While some countries have enacted laws to regulate microplastics, they are not enough to address the challenge. That’s why a new UN legally binding treaty is needed. Global Plastics Treatyoffers significant opportunities: the fifth round of negotiations begins in November.

The treaty aims to reduce global plastic production, but the agreement must also include measures to specifically reduce microplastics.

Ultimately, plastics need to be redesigned to prevent the release of microplastics, and individuals and communities need to be mobilized to support government policies.

After 20 years of research into microplastics, there is still much to be done, but the evidence is more than enough to take action now.![]()

Karen RaubenheimerSenior Lecturer, University of Wollongong

This article is reprinted from conversation Published under a Creative Commons license. Original article.