Really support

Independent journalism

Our mission is to provide unbiased, fact-based journalism that holds power accountable and exposes the truth.

Every donation counts, whether it’s $5 or $50.

Support us to deliver journalism without purpose.

Antarctic ecosystems may soon face a new threat: invasive species carried by floating debris from Australia, Africa and South America.

As the planet warms and sea ice melts, invasive species could invade Antarctic coastlines and disrupt fragile marine life, a new study published in the journal Nature found. Global Change Biology.

Scientists have long believed that only remote islands in the Southern Ocean were at risk of introducing new species to Antarctica, but a new study by a team of researchers from the University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australian National University, University of Otago, and University of South Florida finds that floating debris like kelp, driftwood, and even plastic can reach the icy continent from much further away.

Dr Hannah Dawson, lead author of the study, explained that increased marine litter increases the opportunities for these species to migrate all the way to Antarctica.

“We knew that kelp could drift to Antarctica from sub-Antarctic islands, but our study suggests that drift material can reach Antarctica from much further north, including South America, New Zealand, Australia and South Africa,” Dr Dawson said.

This journey across the Southern Ocean isn’t just theoretical: Researchers used sophisticated computer models to simulate ocean currents and track the movement of debris from various southern continents over a 19-year period. They found that trash can reach the Antarctic coastline every year, with some debris arriving in as little as nine months.

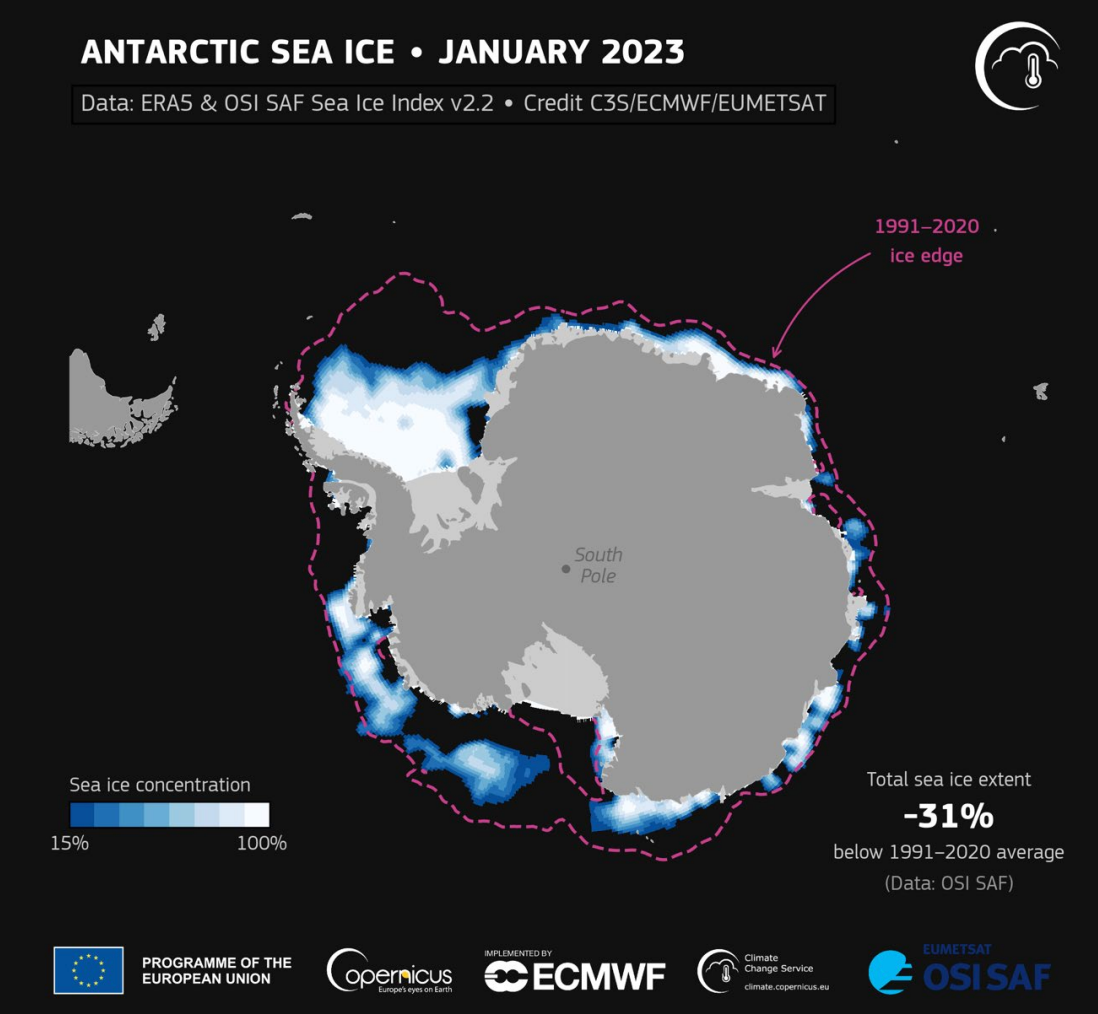

The concern is that as temperatures rise and sea ice declines, these invasive species may find it easier to survive and become established in Antarctica.

“Sea ice is very abrasive and acts as a barrier for many invasive species,” Dr Dawson explained.

“However, the recent decline in Antarctic sea ice may make it easier for organisms floating on the ocean surface or attached to debris to colonize the continent.”

Of particular concern, say the researchers, are the effects of large seaweeds such as giant isopods and giant kelp.

“Southern bull kelp and giant kelp are very large, often over 10 metres in length, which creates a forest-like habitat for many small animals and allows them to be transported on long rafting trips to Antarctica,” Professor Clijd Fraser from the University of Otago said.

“If they were to become established in Antarctica, it could dramatically change the marine ecosystem there.”

The study found that most of the floating debris and potentially invasive species are likely to land on the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula.

This region has relatively warm ocean temperatures and is often free of sea ice, making it one of the most vulnerable places for invasive species to establish.

“These factors may make these areas more likely to become established initially by invasive species, with potentially significant ecosystem effects,” the study said.

With Antarctica’s natural defenses weakened, the arrival of invasive species could alter the ecosystem in ways that scientists don’t yet fully understand.

Scientists are calling for increased vigilance and research to prevent these potential invaders from turning one of Earth’s last pristine environments into a battleground for survival.

Antarctic sea ice has been declining in recent years and is on track to reach near record lows by 2024. As of February this year, ice cover was just 768,000 square miles, 30 percent below the 1981-2010 average.

This is the second lowest amount of ice recorded by satellite since 1979 and the third consecutive year that ice has remained below 2 million square miles.

Analysing the decline in sea ice levels around Antarctica in 2023, researchers from the British Antarctic Survey said that while a sea ice loss would be a once-in-2,000-year event without the climate crisis, it is four times more likely as a result of the climate crisis.