Hello everyone and welcome to another edition of State of Emergency. I’m Jake Bittle and today we’re talking about the political ramifications of one of the worst natural disasters in American history.

When talking about the impacts of climate change in the United States, and particularly the racial dimensions of those impacts, it is impossible to escape Hurricane Katrina. The 2005 storm that breached levees in New Orleans remains the costliest hurricane to hit the United States and perhaps the worst humanitarian crisis the country has experienced in the past century.

Nearly two decades after Katrina, scholars and demographers have devoted a vast amount of research to the political and social impact of the storm, both on New Orleans itself and on the tens of thousands of New Orleanians who never returned. To give a few examples, studies have looked at how the storm affected trust in government, how it affected voter turnout in subsequent mayoral elections, and who storm victims are likely to blame for failed emergency responses.

But Katrina also had a profound effect on the cities to which evacuees fled. In Houston, 300 miles to the west, more than 200,000 victims arrived after the storm, many of them in evacuation buses and camped out on the floor of the Astrodome. Knowing that it would take months or years to rebuild in New Orleans, the Houston city government launched a massive resettlement effort to find long-term housing for evacuees in Texas, rather than housing them in trailers or hotel rooms. Many of them later chose to live in Houston permanently.

Hurricane Katrina evacuees pass the time coloring inside the Astrodome in Houston, Texas, on September 3, 2005.

Omar Torres/AFP via Getty Images

The relocation effort brought Houston Mayor Bill White national praise but also generated significant local backlash. Longtime Houston residents soon began to complain that the refugees brought old gang wars from New Orleans with them, causing the city’s murder rate to spike in 2005 and 2006. There was little data to support this fear, but it nevertheless sparked a moral panic in the city, stoking dozens of newspaper articles stoking concern about refugee crime. Facing reelection, White’s administration responded by stepping up enforcement of minor traffic and drug offenses, arresting some of the refugees and inviting others back to New Orleans. Fear of this crime wave had a clear racial dimension: New Orleans’ black population was much larger than Houston’s at the time.

Though anti-evacuee sentiment subsided in later years, the political backlash against Katrina displacement offers lessons for the future of climate displacement. As climate disasters worsen and thousands of people are forced from their homes each year, it will create significant political turmoil for communities hosting displaced people. Even in large cities like Houston, which had the space and resources to accommodate an influx of evacuees, Katrina displacement caused social panic. For other communities, such as Duluth, Minnesota, which some speculate could become a “climate refuge,” or Boise, Idaho, which hosted many victims of the 2018 Camp Fire that devastated Paradise, California, the backlash could be even greater.

To weather future climate change, politicians must be prepared to address concerns about housing, jobs and crime that could range from overt racism to xenophobia. This is another example of how climate disasters are disrupting political attitudes and changing the beliefs that lead people to the ballot box.

Read more about how Katrina changed Houston politics here. Learn more.

PS: Just signed up for this newsletter? You can find all previous issues of “State of Emergency” here, as well as all the reports in this series.

A series of disasters

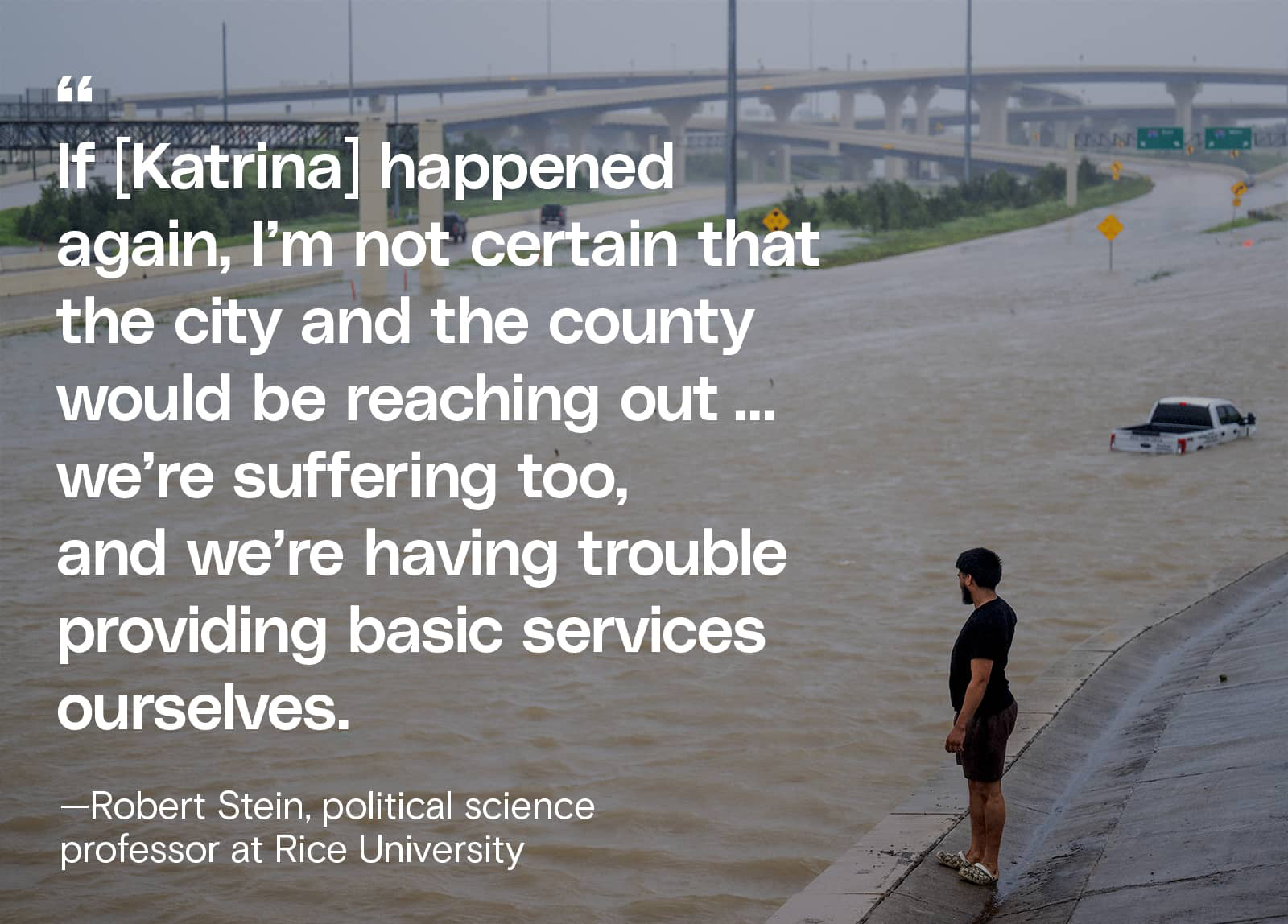

The city of Houston and surrounding Harris County helped return thousands of people who fled New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina, but since then Houston has been hit by a series of costly disasters, from Hurricane Harvey’s massive rainfall to 2021’s deadly ice storm.

On top of that: A person looks at a flooded interstate highway after Hurricane Beryl ravaged the area on July 8, 2024 in Houston, Texas. Brandon Bell/Getty Images

What we’re reading

Climate change has intensified wildfires: A new study finds that many of last year’s deadliest wildfires were made more dangerous by climate change, including those in Canada, Greece, and the Amazon rainforest. My Grist colleague Sachi Malki wrote an article analyzing this disturbing new data. read more

read more

Will Hawaii tighten its building codes? After the Lahaina fire, Hawaii has an opportunity to prevent future fires by imposing stricter building codes, but such efforts could become a “political bombshell” if they result in high rebuild costs or force other homeowners into expensive renovations, Civil Beat reports. read more

read more

Storm damage on Long Island: New York Governor Kathy Hawkle declared a disaster emergency in Suffolk County on Long Island in response to the recent storms and also offered $50,000 in rebuilding grants to homeowners affected by the storm. The Long Island suburb is home to one of the most swing congressional seats in the nation. read more

read more

Frost heats up: Rep. Maxwell Frost of Florida, the youngest member of Congress, spoke about his state’s climate impacts at the Democratic National Convention, citing hurricane-related flooding and heat waves that put farmworkers at risk. read more

read more

Ernesto defeats the power of Puerto Rico: More than a week after Tropical Storm Ernesto passed through Puerto Rico, thousands of residents are still without power restored, further evidence of how fragile the island’s power grid has become. read more

read more