Large wildfires are twice as common as they were 20 years ago

For the first time, data shows that large wildfires are becoming more frequent and intense around the world.

Firefighters work on the scene as flames spread toward a home during the Creek Fire in the Cascadell Woods area of unincorporated Madera County, California, on September 7, 2020.

Josh Edelson/AFP via Getty Images

Analysis of satellite data shows that the frequency of large fires around the world has more than doubled in the past two decades.1The trend is being driven by a surge in large fires across vast swathes of Canada, the western United States and Russia, the researchers said.

The findings are the first hard evidence to support what many scientists and others have suspected as they watch an endless string of devastating blazes ravage ecosystems and communities: wildfires are somehow increasing, and climate change is almost certainly a factor.

“What we’re most concerned about are the extreme events, and we’re seeing a pretty significant increase in those,” said Callum Cunningham, an ecologist at the University of Tasmania in Hobart, Australia, and lead author of the paper. “What’s surprising is that this has never been shown on a global scale before.”

Supporting science journalism

If you enjoyed this article, please support our award-winning journalism. Subscribe. By purchasing a subscription, you help ensure a future of influential stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping the world today.

heating

Researchers have already documented an increase in wildfires across forests in the western U.S.2But it’s been difficult to pinpoint clear global trends. One confounding factor is the decline in the amount of land burned each year, due in part to a steady decline in fire activity in African grasslands and savannas.

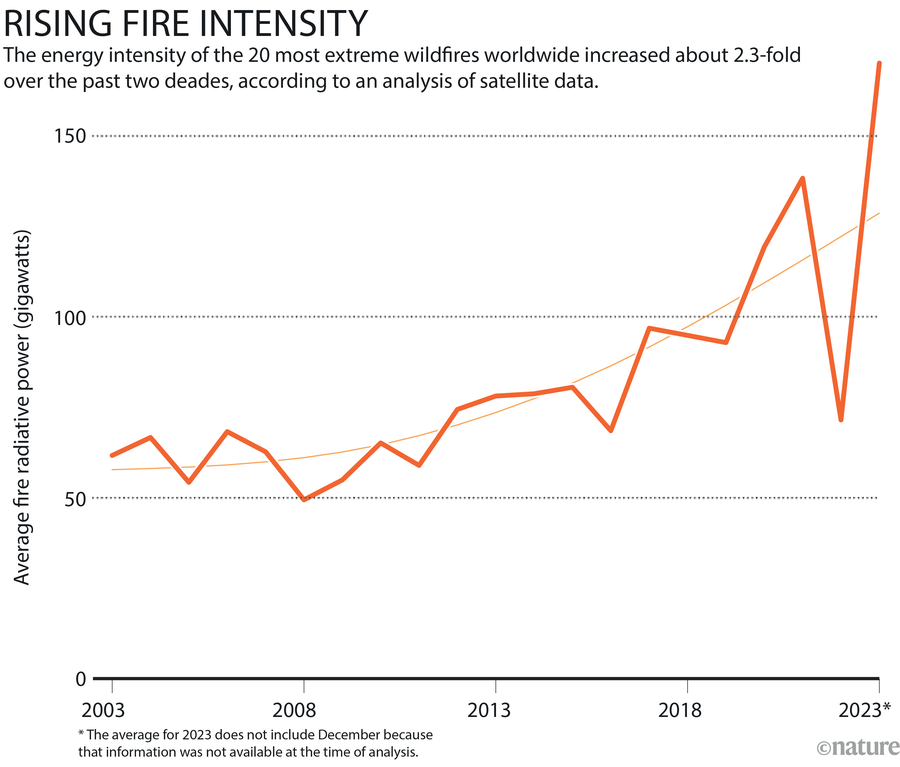

In this study published in 2011, Natural Ecology and Evolution June 24th1Cunningham and his colleagues scoured global satellite data on fire activity. They used infrared recordings to measure the energy intensity of about 31 million fire events every day over a 20-year period, focusing in particular on the most intense ones (about 2,900 events). The researchers calculated that from 2003-2023, the frequency of extreme events increased 2.2-fold around the world, and the average intensity of the top 20 most intense fires each year rose 2.3-fold (see “Rising fire intensity”).

The forests most affected by the extreme fires were those in western North America, where conifers such as spruce and pine grew, with an 11.1-fold increase in fires during the study period. Boreal forests at high latitudes in Canada, the United States and Russia were also hard hit, with a 7.3-fold increase in fires. Park Williams, a hydroclimatologist at the University of California, Los Angeles, says the results aren’t necessarily surprising. But it’s the first compelling evidence that “extreme fires are becoming more intense,” he adds. While the study doesn’t directly link fire trends to global warming, Cunningham says, “there’s almost certainly a key signal of climate change.”3 Rising temperatures are drying out ecosystems that are naturally fire-prone, such as coniferous forests, which can provide fuel and increase the size and duration of fires. The latest study also found that fire energy intensity over the past two decades has increased more rapidly at night than during the day, which is consistent with the evidence.Four Rising nighttime temperatures are contributing to fire risk, the researchers noted. The researchers found unusual fire events in several other biomes around the world, including Australia and the Mediterranean, which both experienced unprecedented wildfires in 2019 and 2020. While no clear trends were found in these regions, it may only be a matter of time before unusual fires occur as temperatures continue to rise, Cunningham said.

This article is reprinted with permission. First Edition June 24, 2024.