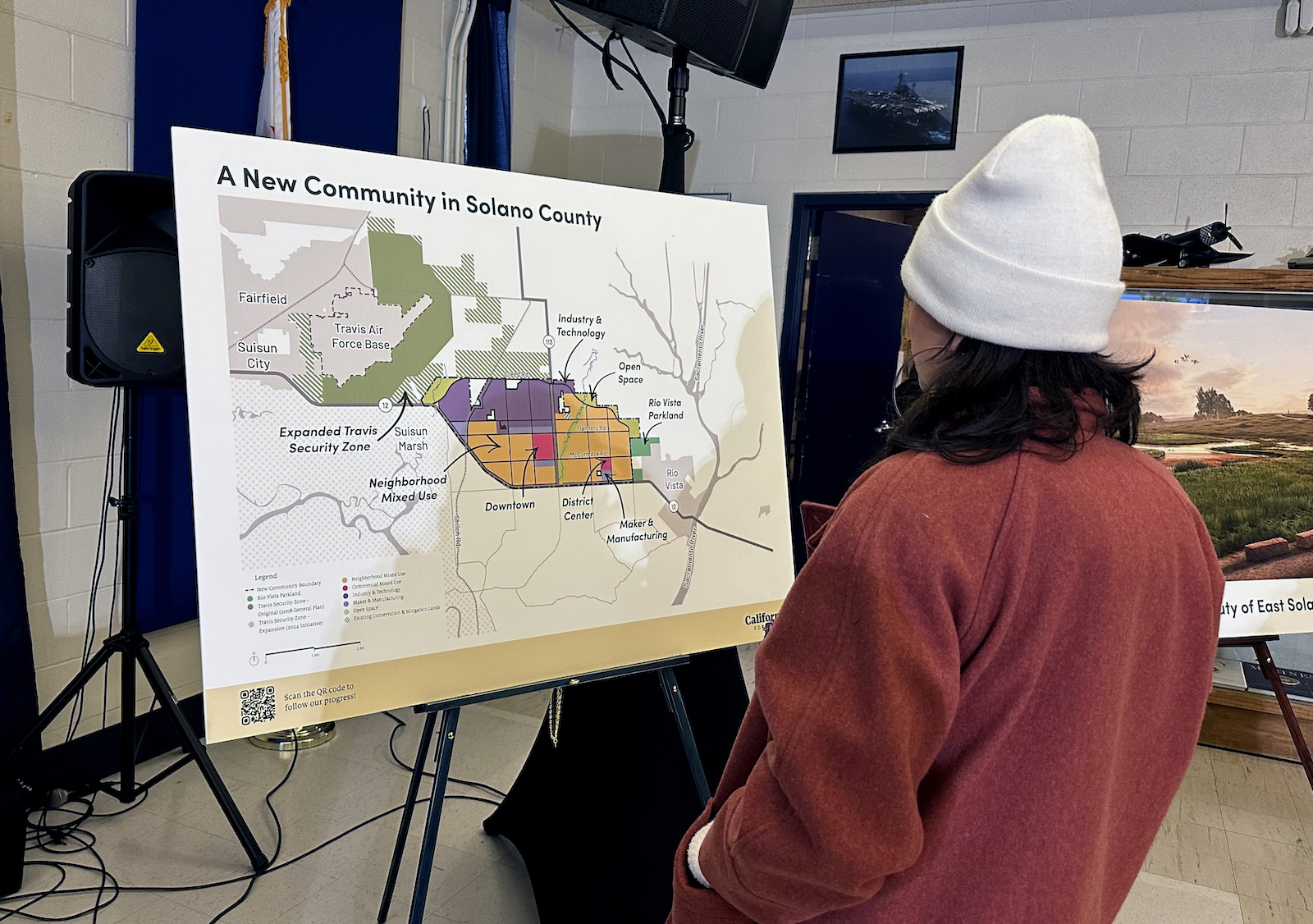

In 2018, one company quietly began making acquisitions. Land worth $900 million From farmers in Solano County, just north of California’s Bay Area, their motives remain a mystery as their land swells to more than 60,000 acres. Fueling fear and speculationAnd last year, this land, Silicon Valley Billionairewas built from the top down by a company called California Forever.

The plan was launched by Jan Sramek, a former Goldman Sachs trader and CEO of California Forever. He said the project has three main goals: “Help solve California’s housing crisis,” “Create a walkable metropolitan area with a high quality of life and a low carbon footprint,” and “Create a new ‘economic engine’ for Solano County.” “There’s no playbook here,” Sramek said. “What we’re trying to do is really, really different.”

Before California Forever could break ground, their proposal, the East Solano Plan, had to be approved by people who already live in Solano County, but that’s where Sramek expects growth to happen. Irreversible ecological Damage. Despite the fact that the government launched a multimillion-dollar campaign to persuade the public to vote for the proposition in the November election, elected officials Expressing dissenting opinionsA coalition was formed to oppose the project, and local distrust was compounded by lawsuits the company filed against landowners. Those who resisted their offerIn an April poll, 70 percent Fifty percent of Solano voters are likely to oppose the measure.

Janie Har/AP Photo

On July 22, the day before the Solano County Board of Supervisors was to decide whether to place the proposal on the November ballot, Sramek and the board agreed to withdraw the proposal. Joint statement Announcing the decision, Sramek said California Forever will seek to put the matter on a vote again in two years, after a report assessing the project’s environmental impacts is completed.

Other similarly-minded, well-funded projects are springing up around the world, including Masdar, a planned $20 billion zero-carbon city in the United Arab Emirates. Decades behind and Reduced NEOM, the Saudi royal family’s $500 billion dream of a renewable energy future, is now Less than one in five It was meant to house 1.5 million of the 1.5 million residents originally planned. Forest City in Malaysia, which won a design award for sustainability, Ghost TownAnd the billionaire behind Diapers.com Terosa Somewhere in the desert of the American West, a vast green-energy city sprawls out.

All these projects aim to realize the urban dream of a better and greener life by building cities from the ground up. But even though the buildings exist, Not attracting residents Despite its sustainability-focused plans, the project Struggle To gain support from environmentalists, California Forever ultimately Accommodates 400,000 people — a goal comparable to those of Masdar and Neom.

“I’ve never seen a project of this scale succeed before,” said Alain Bertaux, an urban planning researcher at New York University’s Maron Institute, “but that doesn’t mean it won’t be successful. There are plenty of projects in the pipeline.”

Berthold said he is typically skeptical of such new city proposals but thinks California Forever’s plan is well thought out. He said one reason the project could be successful is its proximity to other Bay Area cities, and the attractiveness of the region’s job market could encourage people to move there.

Josh Edelson/AFP via Getty Photos

But when it comes to the project’s environmental promises, he’s not convinced, if only because it’s difficult to measure metrics like carbon emissions until a project is actually up and running. “I don’t doubt the commitment of those who are fighting for sustainability,” he says, “but I think that unless you define it very clearly, ‘sustainability’ becomes a self-satisfied slogan that you can apply to any idea.”

The issue of sustainability is at the heart of California Forever’s ambitions and problems. Supporters and skeptics alike say it wants to address the region’s housing crisis: eye-watering rent and home prices. Much more Nationwide, the median price of a single-family home is $1.4 millionOne of the reasons this area has the third highest homeless population is New York City and Los Angeles.

Rather than solving these problems with a new city, California Forever’s critics would like to see more housing built in the seven cities that already exist in Solano County. “Building housing in existing communities is one of the best solutions to our climate problems, but paving over 17,000 acres of non-irrigated farmland is not,” said Sadie Wilson, director of planning and research for the Greenbelt Alliance. The nonprofit is one of 16 organizations in Solano Together, a coalition that opposes the project, along with the Center for Biological Diversity and the Sierra Club of California.

Janie Har/AP Photo

Wilson says the development threatens both the area’s soil’s ability to store carbon and the local biodiversity, as well as risking increased pollution from people driving to nearby cities to commute to work.California Forever holds enough water rights to serve the initial 40,000 residents, but Solano Together says this isn’t enough. Accurately reflect Water supply. They cannot ensure a stable supply. challenging in drought-prone areas.

But California Forever says starting from scratch will allow it to avoid the burden of urban problems like car-centric design and gas utilities, and make it easier to maintain high-density housing and run on renewable energy. “Our plan will have the lowest per capita carbon footprint on the planet. It’s going to be pretty transformative,” said Bronson Johnson, the company’s head of infrastructure and sustainability, adding that the company has struggled for years with barriers to retrofitting existing cities. “When you think about the overall benefits of this project, we think it far outweighs the impacts to the community,” Johnson said.

But they need to convince voters. The New York Times He named many of the investors in the project. California Forever, whose members include LinkedIn co-founder Reid Hoffman and prominent venture capitalist Michael Moritz, launched the effort in August 2023 to rally residents around the state before the 2024 elections. By May, the company $2 million They ran a campaign and gathered enough signatures to put the initiative on the ballot.

A few weeks before the Solano County Commission meeting in July. Economic Report The business-backed Bay Area Council said the county could increase high-paying jobs by 53 percent and touted potential job and housing benefits. Install a lagoon It’s located in the middle of the new town and “is open to everyone in Solano County.”

Fantasy: Why unrealistic Western water projects won’t go away

Five days before the meeting, the county evaluation He said the proposal lacked details on key issues, including infrastructure financing, traffic impacts and water supply. Many of those unknowns would have been answered by an environmental impact statement required by California law, which the company said it planned to prepare after the referendum. County officials said those omissions, along with the lack of a binding development agreement, ultimately caused the proposal to fail.

“This politicized the entire project, made it difficult for us and our staff to work with them, and forced everyone in the community to take sides,” Solano County Board of Supervisors Chairman Mitch Mashburn said in a statement announcing the postponement of the plan. Sramek and Mashburn agreed the timing of the proposal had become unrealistic and came to the decision together, according to the statement.

“I acknowledge that many Solano residents are excited by Sramek’s optimism for California’s recovery, and he is right that our jobs, housing and energy challenges cannot be solved if every project takes 10 years or more to break ground,” Mashburn said in a statement.

Teri Chia/AP Photo

Solano Together Foretold Wilson, who viewed the news as a victory, said even if the environmental impact report would clear up many of the coalition’s questions, particularly about the water supply, the development still poses difficult environmental issues to resolve. “This is a vibrant landscape that supports our food system, our environment and our water system,” she said.

Sara Moser, an urban geography researcher at Montreal’s McGill University, said sparsely populated farmland and desert are naturally attractive for large-scale developments like East Solano because they face less opposition. But building on undeveloped land “of course means you’re taking on a carbon debt that you may never be able to repay,” she said.

Moser believes it’s logistically possible to build a city from the ground up, but he says such projects are increasingly risky and unattainable. “You can’t build affordable housing and make money,” he said, adding that California Forever’s for-profit model fits into a broader pattern of “the rich getting richer” in large-scale urban developments he has studied.

And the most important ingredient needed to successfully build a new city is perhaps the thing that stands in the way: people.

The promise of a city built on ideals isn’t enough to fill it with people, Berteau said. There must already be a community of people, culture, entertainment and jobs to attract them. It’s the chicken-and-egg problem inherent to starting from scratch. “Why go to a city where there’s no one there?” he said.