Watching his flock of about 2,000 sheep grazing among the rows of solar panels, farmer Tony Inder wonders what all the fuss is about. “I’m not saying it’s for everyone, but when it comes to sheep grazing, solar is really good,” he says.

Inder spoke of concerns about the encroachment of prime agricultural land by ever-expanding solar and wind farms, which Australia’s strongest opponents of energy transition.

But on Inder’s New South Wales land, the solar farms are boosting wool production. It’s a symbiotic relationship that Karin Stark, director of the National Agricultural Renewable Energy Council, hopes to see replicated across as many solar farms as possible as Australia’s energy grid moves away from fossil fuels.

“This is all about diversifying agriculture,” Stark says. “Right now, a lot of us farmers are dependent on rain. Solar and wind power provide additional income. “

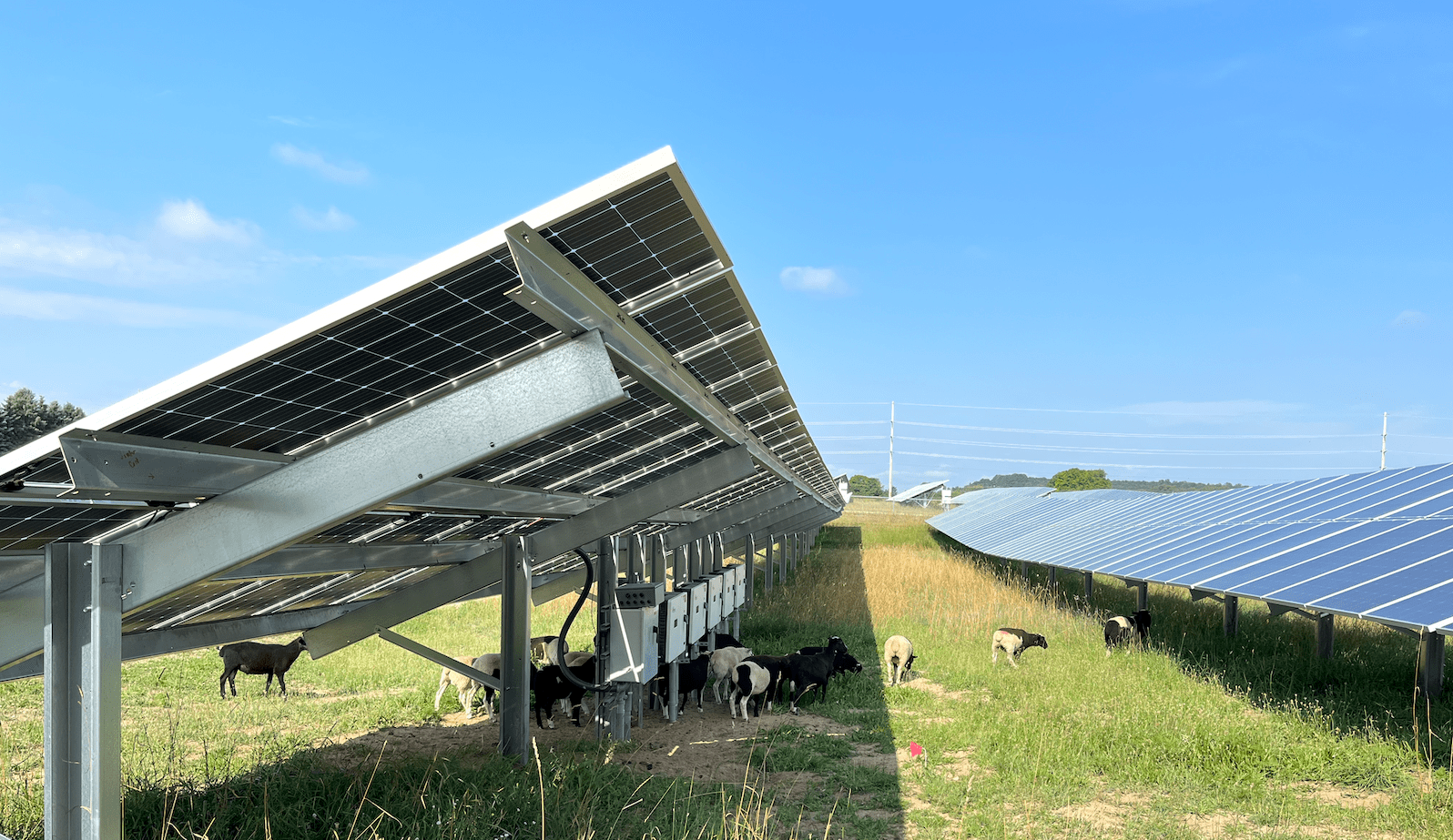

By keeping grass cut, which is a fire hazard during dry summers, the sheep save developers the cost of cutting the grass themselves.

In return, the panels provide shelter for the sheep, encourage healthier grass to grow under the panels’ shade, and form a “drip line” as condensation runs off the panel’s surface.

Sheep may one day graze under solar panels in one of Wyoming’s first “agrivoltaic” projects.

“We’ve had green grass growing, even through the drought,” says Dubbo sheep farmer Tom Warren, who says he’s seen a 15 percent increase in wool production since installing a solar farm on his land more than seven years ago.

Despite these successes, a 2023 Agriculture Resource Centre report written by Stark found that solar power is underutilised in Australia because developers say they intend to raise livestock but do little to adjust their plans to make that happen.

“The result is that many solar farms are no longer suitable for raising sheep,” Stark says. “Developers need to start talking to landowners sooner rather than later.”

Professor Bernadette McCabe, director of the University of Southern Queensland’s Centre for Agricultural Engineering, said agriculture and solar power were “two very different activities” and there was “very little research and success” in combining them.

There has been growing interest in the coexistence of agriculture and renewable energy, driven by the desire to keep farmland in primary production, but McCabe says the “misaligned incentives” between developers and farmers need to be better managed.

These competing goals give opponents of renewable energy “ammunition to attack the industry”, says Ben Wynne, a former solar developer in New South Wales.

Michigan’s solar outlook is bleak

He said energy developers “often talk” about the possibility of coexisting with livestock farming but have no “real desire to do so.”

Mr Wynne is currently part of a community group opposed to a large-scale solar farm planned for south Tamworth because it is located on productive cropland.

“We need to accelerate this transition, but taking away arable black soil will only add fuel to the fire of opposition,” he said.

Wynne also led the construction of a prototype solar farm outside Tamworth, raised above the ground on steel stilts, out of reach of the cattle below.

“Cows are big and they rub and scratch on everything,” Wynn says.

Although the project was successful, Winn said it would be too expensive to implement on a large scale, with installation costs three to four times higher than regular low-lying solar panels.

Cash-strapped farms grow a new crop: solar panels

McCabe says combining sheep with solar power is “very feasible” because sheep can graze under normal-height panels, but he says it’s “still early days” to know whether it would be economically viable for cattle.

Dr Nicholas Abel, director of energy generation and storage policy at the Clean Energy Council, said solar developers should consider dual land-use options but warned they might not be suitable for all projects, adding: “We have an abundance of land in Australia so it’s not necessarily necessary.”

According to an analysis by the Clean Energy Council, powering the East Coast states with solar projects would require less than 0.027 percent of the land used in agricultural production. Much less than one-third of prime farmland The right-wing think tank, the Institute for Public Policy Studies, claims we will be “taken over” by renewable energies. Strongly refuted by expertswas taken up by the National Party, with party leader David Littleproud saying regional Australia Saturation point reached Along with the development of renewable energy.

For more than a decade, Queensland farmer Caitlin McConnell, chair of the Future Farmers Network, has been selling electricity to the grid from 12 custom-built solar panels on her farm’s pastures.

“Trial and error” and improvements over the years have made it structurally sound for cows and economically viable in the long term, she said.

“As far as I know, we’re the only farm that’s running solar power while also raising cattle,” McConnell said. “We have great land, so why would we close it down just for solar panels?”