“Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links.”

On Saturday, June 21, 2025, following a spate of unprecedented aerial attacks that Israel carried out against Iran just days before, the United States joined the war and used bunker-busting bombs to strike three key Iranian nuclear sites and their underground bunkers: the Fordow fuel-enrichment plant, the Natanz nuclear facility, and the Isfahan nuclear technology center.

Operation Midnight Hammer, the Pentagon’s codename for the strikes on Iran, marks the first-ever use of the Massive Ordnance Penetrator (MOP), a colossal 30,000-pound bomb that only the B-2 stealth bomber can carry. As such, America has been regarded as the only country capable of taking out Iran’s underground nuclear facilities, and therefore its nuclear program—but if it actually accomplished that feat is yet to be seen.

While President Trump declared that the operation “completely and totally obliterated” the sites, Iranian officials downplayed the attacks. As of publication time, it’s unclear the level of damage inflicted based on satellite imagery alone, but a CNN report published on Tuesday afternoon claims that the strikes on Iran did not destroy the country’s nuclear program and has instead only set it back by a matter of months, according to early U.S. intelligence.

If history serves as any indication, there is a chance Iran’s underground nuclear facilities could be partially or wholly intact. That’s because up until now, in the quiet arms race between concrete and bombs, the concrete has been winning.

In the late 2000s, for instance, rumors circulated about a bunker in Iran struck by a bunker-buster bomb. The bomb had failed to penetrate—and remained embedded in—the surface of the bunker, presumably until the occupants called in a bomb-disposal team. Rather than smashing through the concrete, the bomb had been unexpectedly stopped dead. The reason was not hard to guess: Iran was a leader in the new technology of Ultra High Performance Concrete, or UHPC, and its latest concrete advancements were evidently too much for standard bunker busters.

Stephanie Barnett, Ph.D, of the University of Portsmouth in the U.K. is involved in developing stronger concrete to protect civilian buildings from terrorist attacks, and has heard about Iran and its ultra-tough concrete. While civilian audiences have been enthusiastic about the advancements in concrete, she occasionally hears less positive responses from military personnel attending her presentations.

“One officer told me, ‘If you make this stronger blast- and impact-resistant material, we need to think about how to get through it,’” Barnett says.

On June 21, 2025, the U.S. Air Force used six B-2 bombers to drop 12 bunker-busting bombs on Fordow, Iran’s most significant nuclear enrichment facility, an official told CNN. Based on satellite imagery alone, it’s still unclear the level of damage the underground bunker sustained. Getty Images

The U.S. Air Force introduced its first modern bunker buster in 1985. General-purpose bombs have a thin steel casing filled with explosives, while bunker busters have a narrower profile, with a thicker casing and less explosives. This design concentrates all the weight on a smaller area, making it an ice pick rather than a hammer, so the bomb can smash through concrete or burrow through earth to strike deeply-buried targets.

While the same general-purpose bombs from the 1990s are being used today, bunker busters had to go through several generations of upgrades. In the early 2000s, the Air Force even developed a special type of steel for the purpose, known as Eglin Steel, in association with steel specialist Ellwood National Forge Company.

Eglin Steel is a low-carbon, low-nickel steel with traces of tungsten, chromium, manganese, silicon, and other elements, each contributing a desirable property to the whole. Eglin Steel is the gold standard for bunker-busting munitions, although in recent years it has been supplemented by new USAF-96 steel, which boasts similar performance but is easier to produce and work with.

Materials scientists distinguish between the two qualities of toughness and hardness, and it is the balance between them that drives arms races between weapons and armor.

For example, when a soft lead bullet strikes a Kevlar vest, the bullet crumples and deforms, losing energy because it lacks hardness. Give the bullet a hard steel jacket, though, and the Kevlar gives way. The counter is to make armor harder by adding ultra-hard ceramic plates made out of materials like boron carbide. These are so hard that steel-jacketed bullets break up on impact. This led to special armor-piercing bullets tipped with hard tungsten. When these hit a ceramic plate, the plate breaks up in a process known as brittle failure.

The bunker-buster arms race is similar, but while the attackers have the advantage of steel, defense is based on concrete, which starts with a built-in disadvantage. “Concrete is inherently brittle,” explains Phil Purnell, Ph.D., an expert in concrete technology at the University of Leeds. “It is good at being squashed, not being stretched. The weakness is in its tensile capacity and toughness.” Purnell notes that while some modern concrete is actually stronger than aluminum, its brittleness is its Achilles’ Heel, and it gives way by cracking.

However, this changed with the advent of the type of concrete known as UHPC. Previously, a yield strength of 5,000 pounds per square inch (psi) was enough for concrete to be rated as “high strength,” with the best going up to 10,000 psi. The new UHPC can withstand 40,000 psi or more.

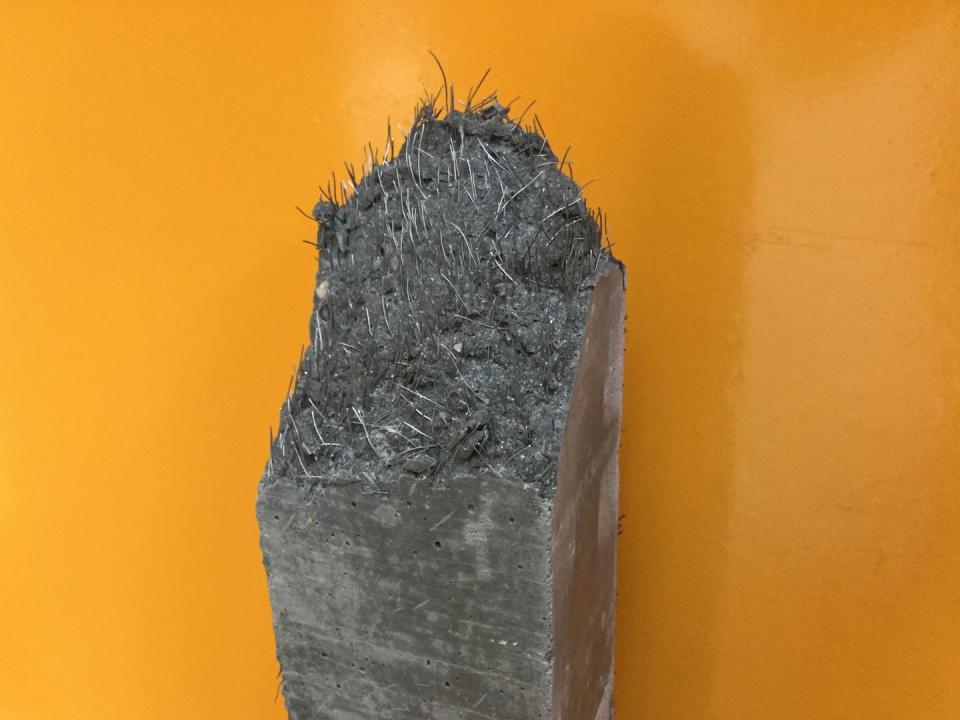

A sample of ultra-high-performance, fiber-reinforced concrete. Bianca Paola Maffezzoli, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The greater strength is achieved by turning concrete into a composite material with the addition of steel or other fibers. These fibers hold the concrete together and prevent cracks from spreading throughout it, negating the brittleness. “Instead of getting a few large cracks in a concrete panel, you get lots of smaller cracks,” says Barnett. “The fibers give it more fracture energy.”

Fracture energy is defined as the amount of energy needed to split a material open. The concrete absorbs the incoming kinetic energy of a projectile as it fractures, slowing it right down and stopping it from penetrating. Naturally, researchers have been experimenting with finding the optimal mix of fibers for UHPC. More is better, but there is a limit. “The problem is that if you put in more than about one percent of steel fiber, it starts to clump together,” says Purnell. “The clever trick [is] how do you mix in more than one percent of fiber into the concrete.”

Various teams around the world have been working with techniques to mix fibers successfully. Much of this work is carried out by the military, but as Barnett notes, in her experience, the military sometimes comes and asks questions to civilian researchers but never says anything about its own work. In the field of impact-resistant concrete—a minority interest in civil work—they may be way ahead of their civilian counterparts.

💡 In January 1991, when the U.S. was leading the operation to Kuwait, U.S. intelligence discovered something alarming. The Iraqis had built a series of new command bunkers around Baghdad deep underground and protected by several feet of reinforced concrete, estimated to be invulnerable to the U.S. Air Force’s existing 2,000-pound bunker busters.A crash program was launched to build a new 5,000-pound bomb for the job.

The Air Force asked for ideas on January 18, and work commenced immediately at the Air Force Research Laboratory Munitions Directorate at Eglin Air Force Base, Florida. There was no time to fabricate bomb casings from scratch, so surplus 8-inch howitzer barrels were used as the basis of the bomb body, hand-filled with explosives, with a new nose section added.

The first prototypes were delivered to the Air Force less than a month later. In a rocket-sled test, the new weapon penetrated over 20 feet of concrete.Two operational bombs were flown to the theater on February 27 and delivered by F-111Fs. Six seconds after impact on one of the new Iraqi bunkers, smoke poured from the entrance, showing the bunker had been breached and destroyed. The day was saved by a munition developed in six weeks flat.

In 2012, the USAF launched a project to evaluate the challenge posed by bunkers made of UHPC. The Air Force ended up developing its own version of UHPC, known appropriately enough as Eglin high-strength concrete, for the testing process.

While the results of the USAF study are classified, an open-source Chinese study compared normal high-strength concrete with fiber-reinforced UHPC. Projectiles smashed through the reinforced concrete targets, but the UHPC targets survived with only minor cracking, and projectiles “either embedded in or rebounded from” the targets.

The Air Force was already concerned that even its 5,000-pound bombs were not sufficient, and in 2011, it received the Massive Ordnance Penetrator. This was even bigger than the celebrated 21,000-pound Massive Ordnance Air Blast (MOAB, or “mother of all bombs”), meant to bust the deepest and toughest bunkers with transparent kinetic energy. MOP is about as big a bomb as you can fly—only the B-2 Spirit strategic bomber has the capacity—so smaller 2,000- and 5,000-pound weapons will still need to do most of the work against lesser targets.

The Massive Ordinance Air Blast (MOAB) weapon, March 11, 2003 at Eglin Air Force Base, Florida. USAF – Getty Images

After the concrete study, the Air Force upgraded the MOP. Then it upgraded it again. By 2018, it was on its fourth upgrade. Similar upgrades were made to smaller weapons.

The problem is that even the biggest bomb possible, made of the toughest material available, may no longer be able to hack it. Gregory Vartanov, Ph.D., of Toronto-based Advanced Materials Development Corp, claims high-grade UHPC is simply too strong for bombs made with existing steels. “Penetrators with monolithic cases made from materials such as … Eglin Steel … cannot penetrate bunkers made from UHPC,” Vartanov notes in a February 2021 piece in Aerospace & Defense Technology magazine, basing his claim on open-source penetration formulas.

But that is not the end of the story. UHPC is good, but even better protection is already being tested in the laboratory.

Recent Chinese research describes Functionally Graded Cementitious Composite, or FGCC, made by layering different types of high-performance concrete with different properties. The thin outer layer is extra-hard aggregate-reinforced UHPC; beneath this is a thick layer of hybrid fiber-reinforced UHPC optimized to resist cracking. Finally, there is a layer of tough steel fiber-reinforced UHPC. As Purnell explains, each layer has a different effect.

“You’ve got that hard outer layer to damage the projectile, then there is the thick layer with the mass to absorb its energy, and then the inner layer is there to catch the bits,” he says. This inner, anti-spall layer, ensures that if the concrete does crack, no fragments (or “spalling”) get through into the bunker beyond.

According to Chinese research published in 2021, FGCC resisted penetration and explosion far better than UHPC: “penetration depth, crater area, and penetration damage were decreased greatly by the synergistic effects of high-strength fibers and coarse aggregates.” Barnett says that she has worked on a similar concept, and that this technique of layering materials with different properties could be more effective than any single material.

The latest research follows at least four years of Chinese study into layered concrete, with a particular focus on absorbing impacts and blasts. Expect new bunkers to be very tough nuts to crack.

There is limited scope for making bunker busters bigger and badder, but there are other approaches. The arms race may not continue along the same path but take off in a different direction.

“Hypersonic weapons offer a new potential mode of attack against hardened bunkers,” says Justin Bronk of the U.K. defense think tank RUSI. Hypersonics are missiles which travel through the atmosphere at speeds in excess of Mach 5. Equipped with tungsten penetrators, they could act as “rods from God,” punching through layered concrete like an armor-piercing bullet. With no explosive warhead, such weapons do damage through kinetic energy alone.

Bronk notes also that it is not always necessary to actually destroy a bunker. You can damage the entrances, take out the aerials, and cut off communication to a command bunker with hits in the right places. In military terms, it might as well be a crater, even if the occupants are unharmed.

The U.S. Air Force will understandably not discuss its current bunker-busting capabilities or how they stack up against potential targets in Iran, China, or elsewhere. And most of the military work on high-strength concrete is similarly classified. But the severity of damage inflicted on Iran’s nuclear program will probably give us some clues.

Editor’s Note: This story was originally published in September 2022. It has been lightly edited for clarity and timeliness.

You Might Also Like